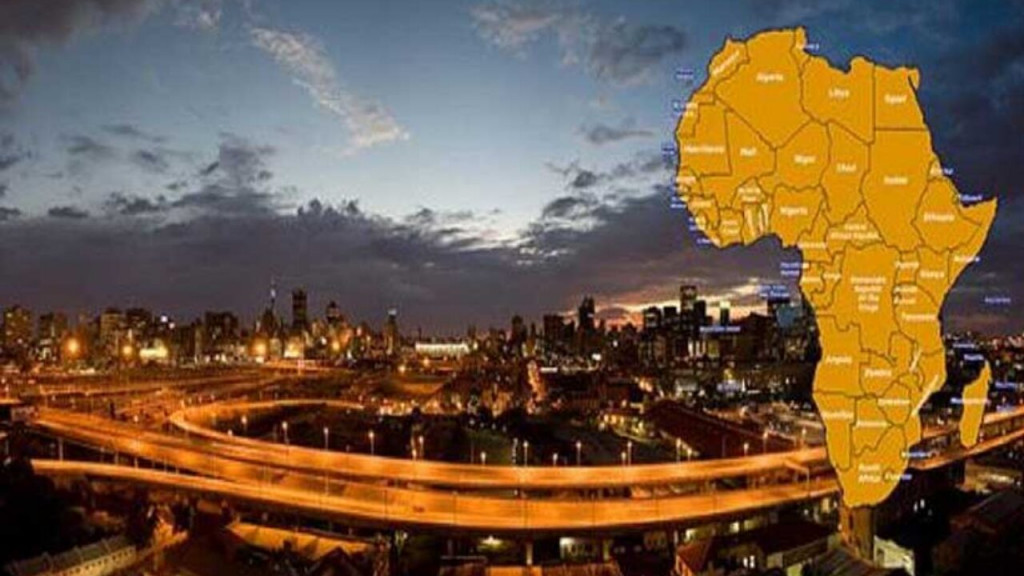

Not only China. A number of Asian countries are betting heavily on the African continent in terms of investments and commercial and diplomatic cooperation. An overview

China’s interest in the African continent has increased exponentially over the last 20 years, but its roots go back to 1955.

In order to better understand current events, we must take a short trip to the past. Historians usually divide the Sino-African relationship into different phases. The first approach dates back to the early 1950s, a period when the PRC funded construction projects and gave its support to several independence movements. The 1980s saw the beginning of the second phase, which was mostly negative and deteriorated the relationship because China adopted a policy of isolation. It was the period when the Chinese government started to abandon Maoism (an ideology based on the collectivization of resources) in favor of a capitalistic approach (labeled as temporary and necessary to achieve an ideal Communist regime), which would be decisive in subsequent Sino-African relations. China’s wish to help the Third World, crushed by colonialism and the Western model, is linked to its intention to promote an alternative model.

The 1990s saw a progressive intensification of relations and an "updated" approach from China, in contrast with the one of half a century earlier: China expanded its scope of action, including various sectors such as trade, investment, general assistance, transfer of skills and training. The PRC spread its activities in both the public and private sector.

The new millennium ushered in another quick and steady phase of growth. 2013 in particular was a landmark year as China overtook the USA in becoming the lead investor in Africa.

Looking at the figures, the global trading volume between China and Africa has increased by 24.7% and loans from China have reached 153 billion in the last 20 years.

So that begs the question, what were China’s main investments?

- Raw materials: Africa possesses the raw materials needed by the PRC, especially for the manufacturing sector. It should be remembered that China has gone from being a major agricultural economy to the world’s largest importer of agricultural products in the last 30 years, which earned it the title of "low-cost" country for labor cost.

- Market: the African market is considered particularly attractive by Chinese investors both for its extension and recent liberalization, two important factors that limit the strength and consolidation of foreign actors, thus weakening competition and facilitating market entry.

The modus operandi of Chinese investments is based on reciprocity and in this it differs from the Western model. The North of the world used its investments to facilitate its own interests without aiming at the improvement of local conditions. On the contrary, the Chinese approach was all-encompassing and win-win: China made available to partners the same wealth of knowledge that had helped the country in its development.

Is the People's Republic of China the only Asian country that has an economic presence in Africa?

The Land of the Rising Sun disagrees with that. The masterpiece of Japanese diplomacy in Africa has a name: Ticad. This acronym, which stands for Tokyo International Conference on African Development, indicates a series of summits organized by the Japanese government and the UN since 1993. These summits are attended by more than 40 African heads of state and have always been held in Japan except in 2016. Ticad has laid the foundations for projects "of the African people", in which Japan plays the role of facilitator through investments and know-how: many technical and commercial agreements with Tokyo were signed during these conferences, which are still today a powerful propaganda tool for Japan’s foreign policy.

The numbers speak for themselves: between 2007 and 2017, Japan's foreign direct investment in Africa increased from 3.9 to 10 billion dollars. According to Shigeru Ushio, head of the African Affairs Department of Japan's Foreign Ministry, access to African markets is vital for Japanese companies and African start-ups as it facilitates their development thanks to less bureaucratic legislations.

Infrastructures were Japan’s starting point. The Japanese government began its activities in Africa by developing ambitious projects on a supra-regional scale. A prime example is the port of Mombasa, an asset of paramount importance since it is the terminus of the transcontinental Inter-African Highway 8, which will connect Lagos, Nigeria, to Mombasa, Kenya. The entire project is managed by Toyo Construction Co., which is by no means the only Japanese company operating in the region. According to the Overseas Construction Association of Japan, as many as 16 Japanese construction companies are active in 22 African countries.

But Japan went beyond the infrastructure sector. Its horizons are much broader and quickly expanded to import-export markets and new technologies, with 796 Japanese companies active in Africa in 2017. Some of these, like the Nippon Biodiesel Fuel start-up in Mozambique, created a solid network of suppliers and farmers linked directly to their activities.

The mining and energy sector has certainly been a resounding success for Japan, as evidenced by the presence of headquarters of the most important Japanese corporations like Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corp. which is in charge of oil prospecting in Kenya and natural gas development in Mozambique.

“Three’s a crowd”: India joins China and Japan.

Growing commercial needs led India to look at Africa as an increasingly important economic partner and to reinvigorate its naval presence in the Western Indian Ocean as a means to ensure trade security.

Specifically, the Horn of Africa is extremely important for the security of New Delhi as it is located at the northwestern end of the Indian Ocean. Historically, the port of Adulis, near Massawa, has been a central hub for maritime trade between Europe and Asia, frequented also by many Indian traders. Stability in the Horn of Africa was already a priority at the time of the British Empire because it would ensure security and economic prosperity in Colonial India. After becoming independent in 1947, India adopted a strategy of military isolationism that limited the spread of its regional influence. In the 1990s and early 2000s, in concomitance with India's economic boom, domestic demand for raw materials needed to fuel growth increased exponentially. All these factors contributed to the creation of a dynamic environment and to the need for energy diversification. From that moment on, Indian investors started to take into consideration the opportunities offered by the African continent.

The Indian approach in Africa is based on mutual respect and non-interference within the framework of South-South cooperation. In the Horn, India is helping the countries most in need through development aid aimed primarily at the agricultural, health and education sectors. All countries in the region are partners in India's Pan African e-Network project, an initiative launched in 2009 by the New Delhi government and aimed at sharing Indian expertise in the fields of health and education with African countries.

Indian activities in Africa are not limited to humanitarian aid: the government seeks to satisfy its own needs for energy and food security, fundamental for the country's economic and demographic growth, as well as to take advantage of emerging business and investment opportunities. New Delhi is supported by the entrepreneurial community and big private companies. Between 2000 and 2014, bilateral trade grew from $10.5 billion to $78 billion thanks to Indian exports: electrical equipment and other machinery, pharmaceuticals, food, manufactured goods.

In summary, China's leading role as an investor in Africa is constantly challenged by the competition of India and Japan. India’s influence in the continent is growing: on one hand, it helps the Indian government to have a wider role in international relations, and on the other hand it satisfies the raw materials needs of a rapidly growing economy. The Japanese government is aware that Japan-Africa relations are crucial for the protection of maritime trade routes because the oil imported by Tokyo from the Middle East is transported along the African coast. This goes to show that despite their rivalry, there is some convergence: having a strong economic presence in the African continent is a priority for China as much as for India and Japan.