Kuala Lumpur is attracting more and more foreign investors to its semiconductor sector, aiming to move up the value chain for chips, particularly those for electric vehicles

By Walter Minutely

Malaysia is emerging as a crucial node in the microchip supply chain. This leading role is supported not only by its strategic location in the heart of ASEAN and the relative political and economic stability of the country, but also by developed infrastructure, highly skilled workforce, and government policies favorable to foreign investment.

Furthermore, the growth of the domestic market and the presence of natural resources contribute to making Malaysia an increasingly attractive option for investors, especially from the United States and Europe, in the microchip sector, seeking to diversify their production across different areas. This phenomenon reflects how geopolitics is shaping technological production.

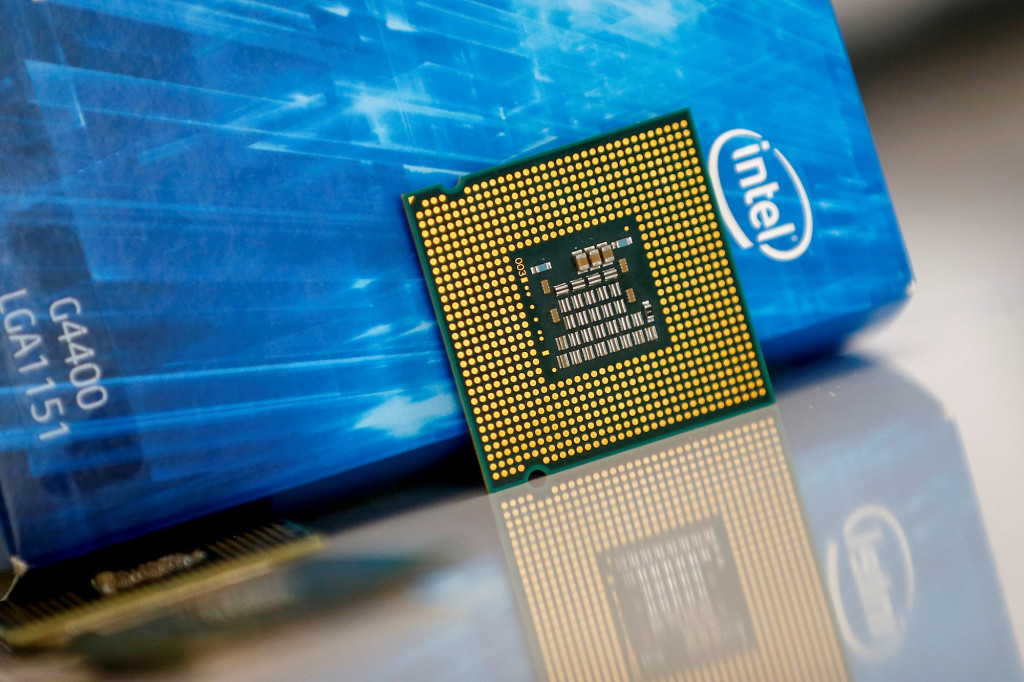

According to the Financial Times, Malaysia has become a magnet for major companies in the sector, including Intel, Micron, and others. With a significant increase in foreign direct investment, the semiconductor sector in Malaysia is experiencing unprecedented expansion. In just the northern state of Penang, foreign direct investments worth $12.8 billion were activated last year, surpassing those of previous years.

The Malaysian government has recognized the strategic importance of the semiconductor industry and is actively committed to further developing it. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has stated that the development of the semiconductor industry is a crucial goal for the country.

US technology companies are playing a key role in this growth scenario. For example, Intel has invested $7 billion in new facilities in Malaysia, including an experimental 3D packaging plant. Another industry giant, Micron, opened a second plant in Penang last year, while Infineon announced a $5.4 billion expansion plan.

These investments not only indicate Malaysia's growing role in the semiconductor sector but also have significant implications for the local economy. Industrial land prices have increased by 60% since 2002, while road traffic has experienced increasingly frequent congestion.

However, Malaysia faces crucial challenges in maintaining this sustainable growth. One of the main issues is the shortage of skilled labor, with the expanding sector requiring at least 50,000 new engineers annually, while the country's universities produce only 5,000 graduates in the field.

The choice to invest in Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia is also motivated by their strategic position in the South China Sea, which plays a crucial role in the chip sector. This strategic location allows companies to have privileged access to key trade routes for transporting components and finished products in the semiconductor sector. Furthermore, being one of the most important navigable routes globally, the South China Sea facilitates efficient transportation of materials and products to Asian and global markets, thus contributing to the competitiveness of companies operating in this sector.

The economic benefits resulting from investment in these regions include highly skilled and relatively low-cost labor, modern infrastructure, and a favorable policy for foreign investment. The presence of special economic zones and additional tax incentives makes investment in these areas even more attractive, offering companies a favorable environment to expand their operations and maximize returns on investment.

Furthermore, interest in Malaysia has increased after the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the vulnerabilities of global supply chains. Tensions between the United States and China have prompted both countries to seek reliable sources of semiconductors outside mainland China, further accelerating interest in Malaysia.

With the semiconductor industry continuing to grow in Malaysia, the country is preparing to face challenges such as expanding infrastructure and transitioning to clean energy. Despite these challenges, many business executives are confident in Malaysia's role in the global technological supply chain, recognizing its potential to become a benchmark in the global electronics industry.

Malaysia is attracting increasing foreign investment in its semiconductor sector, aiming to advance in the chip value chain, particularly for chips used in electric vehicles.

Currently, the country holds a 13% share of the global market for semiconductor packaging, assembly, and testing services. Additionally, Malaysia ranks as the sixth-largest exporter of semiconductors globally, packaging 23% of all American chips, contributing to 25% of the nation's GDP. This makes it a key player in the global semiconductor market.

In the past, Malaysia was recognized as the Silicon Valley of the East, having been a pioneer in chip production in the 1970s. However, over the subsequent decades, it gradually lost ground to South Korea and Taiwan. Nevertheless, Malaysia is currently striving to regain leadership in the sector, pushing to diversify its production. Among the potential advantages for Malaysia is that companies are seeking a less exposed location to global turbulence and with more stable future scenarios compared to Taiwan, which currently dominates the manufacturing and assembly sector.

Malaysia's New Industrial Master Plan (NIMP) 2030 provides a roadmap for increasing the value-added of the manufacturing sector, encouraging more sophisticated activities such as semiconductor equipment manufacturing and integrated circuit design. The country aims to develop the semiconductor sector, focusing on high-value-added activities such as wafer fabrication and integrated circuit design.

In recent years, the country has seen significant investments from European and American companies, as seen in the cases of Intel and Texas Instruments. However, there are challenges that investors must face, including the shortage of qualified talent in the semiconductor sector and heavy dependence on foreign companies to support the industry. Despite these challenges, Malaysia remains an important destination for foreign chip manufacturers, attracted by its strategic position in Southeast Asia and supportive government policies.

Diversifying supply chains offers opportunities for Malaysia to expand its presence in the global electronics industry, moving towards more sophisticated and innovative production. With targeted investments in research and development, as well as training programs, Malaysia could further strengthen its role in the semiconductor sector, contributing to economic growth and innovation.