Many predicted a continuation of Rodrigo Duterte's international line, but with the new president, the Philippines is back to being 'everyone's friend and no one's enemy'

Article by Geraldine Ramilo

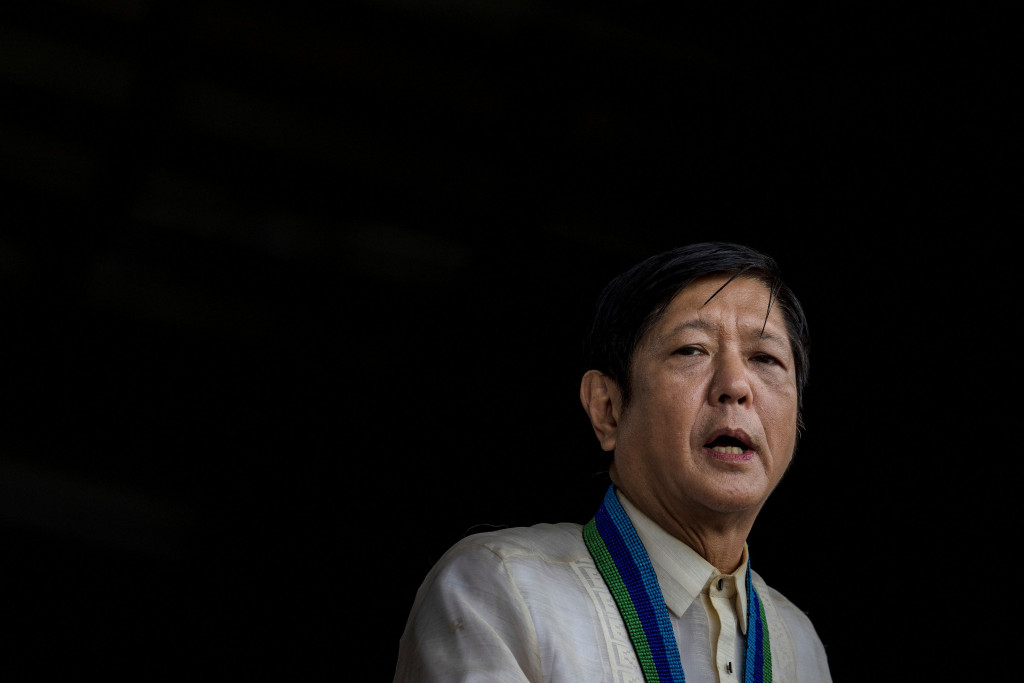

Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, took office as the new Philippine President in June 2022, winning a landslide election victory the month before. During his election campaign, references to his foreign policy intentions were vague. Some initial speculation predicted a continuation of his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte's line of rapprochement and cooperation with China. Now, however, a few months after his official inauguration, Marcos Jr. seems to have no intentions of getting too involved in the delicate confrontation between the US and China.

The Philippines, due to its strategic location, is a contested area of influence in the rivalry between the two superpowers for dominance in the Indo-Pacific region. On the one hand, the Philippines and the US have a privileged economic and security relationship. Indeed, the two countries established a formal diplomatic relationship in 1946 and entered into a mutual defence pact in 1951. On the other hand, China is now a major economic partner of the Philippines due to its huge investments in the Philippines' domestic infrastructure. The relationship with Beijing was also fostered by the previous head of state Duterte, who conducted a policy line openly hostile to the West and the United States in particular.

Some recent episodes have made it possible to contemplate a rapprochement of the Marcos Jr. administration towards Washington. Already during the election campaign, the then President-elect had mentioned the importance and benefits the Philippines derives from its relationship with the US. The White House had also expressed interest in restoring the 'normalcy' of relations between the two countries that had been interrupted under Duterte. Current US President Joe Biden was even the first foreign head of state to congratulate Marcos Jr. on his victory. This rapprochement with the United States should not, however, suggest that the relationship built with China has broken down. Marcos and his family have always had a close relationship with the Asian giant, so much so that the president himself, after being elected, had a long telephone conversation with Chinese President Xi Jinping, where both expressed interest in strengthening the bilateral relationship.

It is therefore expected that Marcos Jr. will not take any drastic stance in favour of either the US or China for the time being, but will maintain a collaborative and balanced position between the two poles. As proof of this, during his first State of the Nation Address in July 2022, Marcos Jr. declared his intentions to implement an independent foreign policy while maintaining good relations with both powers. He announced the Philippines' ambition to be 'friends of all and enemies of none', and then appealing to the generality of the constituent countries of the international community, the newly elected president added: 'If we agree, we will cooperate and work together. If we disagree, we will dialogue more until we agree'.

Marcos Jr. thus seems to have distanced himself from the anti-Western and strongly anti-US policy of his predecessor, following instead an independent foreign policy line more similar to that of Duterte's predecessors, including that of his own father. The idea behind such a policy is to secure maximum benefits from both poles and leave room for manoeuvre to move according to national interests. Marcos Jr. thus seems to be oriented towards building a delicate balance between the US and China, leaving open the possibility of exploring opportunities for cooperation on both fronts.

In the context of the rapprochement in Washington after the break-up with Duterte, the visit of US Vice President Kamala Harris to the Palawan Islands and her meeting with the Philippine President in the past few days is part of the US aim to strengthen and reaffirm relations with its historical allies. Indeed, the Philippines is a crucial point for the Biden administration and its diplomatic strategy to contain Chinese ambitions in the Pacific. Despite Palawan's geographical proximity to the South China Sea and the implicit message from the US, the visit does not necessarily pose a direct threat to China. But some Philippine experts are concerned about the awkward position their country will find itself in with Beijing and the risk to national interests should the dispute between the two powers escalate.