Climate change is real, and Southeast Asian countries have already experienced its effects in the most impactful way. Here is why inter-regional cooperation between ASEAN and the EU is an opportunity to achieve sustainability.

According to science, climate change is already irreversible. Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and the Philippines are among the most affected countries. Indeed, even though no country is immune, this region is particularly vulnerable. In this regard, inter-regional cooperation between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the European Union is deemed to be a great opportunity to enhance sustainable production practices and critical consumption.

It is quite hard to assess responsibilities when it comes to environmental deterioration and climate change. Developing countries blame the most developed ones of having profited from the exploitation of environmental resources; on the contrary, developed countries evolved in informed markets of consumers, sensitive to ecological issues, therefore they accuse developing countries of polluting. Indeed, these countries usually leverage bland regulations on environment in order to attract more foreign direct investments (FDIs) within their territory. However, it is hard to define what is a scientific posture towards the issue and what is mere political rhetoric. Nonetheless, this debate should not distract us from a very urgent fact: climate change is here.

Two other facts are real when dealing with the debate on climate change. First, the unprecedented frequency of storms, droughts and meteorological and environmental phenomena are among the effects resulting from human activity. Indeed, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry Paul Crutzen introduced the term “anthropocene” to indicate the current geological era. Here, human beings compromised the survival of the planet through polluting activities, often determined by unsustainable production rates. The second certain element is that poor populations of developing countries are the most vulnerable, and those least resilient to bounce back from the disruption of environmental disasters. Insufficient economic resources and unstable public institutions are a weakness. This can cause the transformation of environmental disasters in social disasters, thus compromising the long-term stability of the socio-economic fabric of local communities.

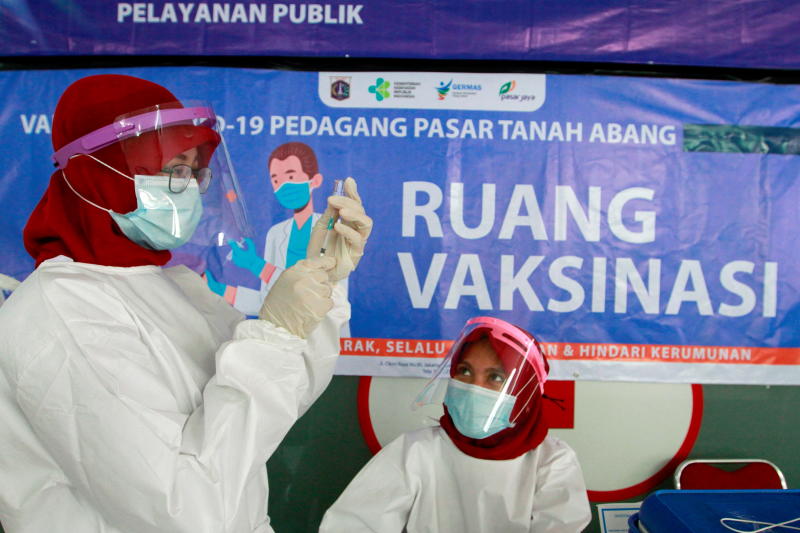

These issues, together with that of food security, are particularly urgent among the countries of Southeast Asia, for two main reasons. First, most of the inhabitants are concentrated in coastal areas. As an instance, Jakarta is a case of the variety of risks associated with climate change. Urban residents of Indonesia are estimated to represent 65% of its total population in 2025. By that date, the Indonesian capital will probably be 95% submerged by the Java Sea. The most populous country in Southeast Asia is not news to this kind of environmental phenomena, which have become increasingly recurrent and aggressive since the 1960s. Thailand is also accustomed to floods and storms, which once hit it less frequently and caused less damage: Bangkok, sinks about 1-2 centimeters every year, and at this rate in 2030 it will be below sea level. Similarly, the development of the city of Da Nang in Vietnam, which thanks to the centrality of its geographical position is regarded as an important hub for the Vietnamese transport and service sectors, is slowed down by continuous flooding. Finally, according to the il Global Climate Risk Index, Myanmar and the Philippines are regularly exposed to severe tropical cyclones and are unlikely to recover in time from the disasters of previous years, with the result that the damage adds to each other, weighing on the local population.

Secondly, climate change impacts most severely on agriculture, a pivotal economic sector for most of the ASEAN countries. Namely, wheat, rice and maize crops are extremely susceptible to adverse weather conditions. In addition to being compromised by the unpredictability of these climatic phenomena, agricultural activities also cause the largest share of emissions of which the economies of Southeast Asia are accused, responsible of the intense consumption of energy and fossil fuels.

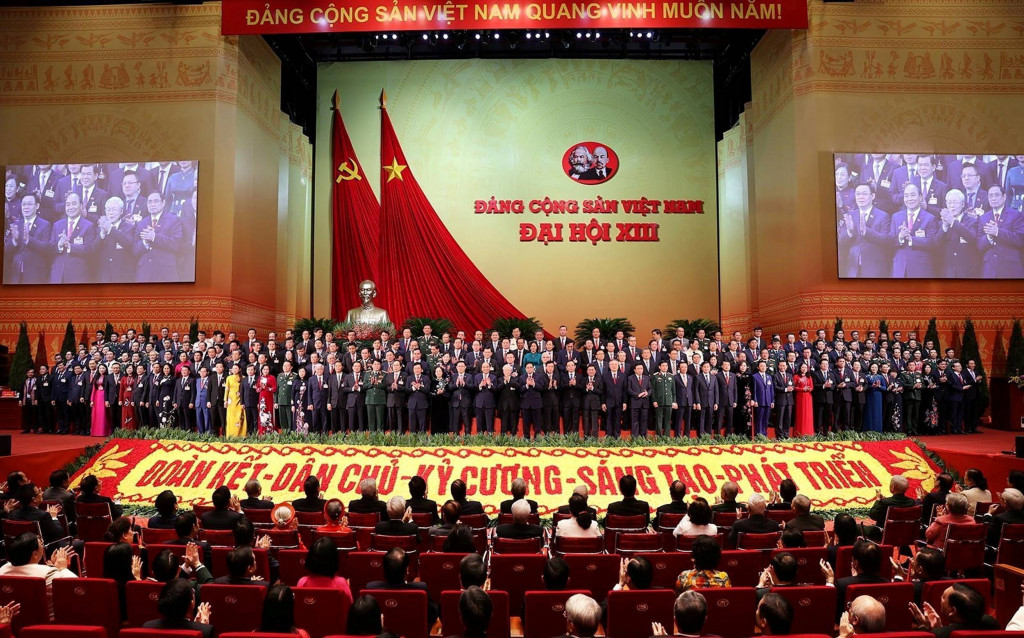

This scenario makes the promotion of international cooperation all the more necessary. In addition to being part of the Paris Agreement, ASEAN founded its own working group in 2009, the ASEAN Working Group on Climate Change. It is a consultative platform designed to promote regional cooperation and climate action with international partners, as well as with local communities. ASEAN Senior Officials on the Environment also carries out coordinated action between member countries and various dialogue and development partners; in addition, the ASEAN Climate Resilience Network is dedicated to sharing information, experiences and skills related to climate smart agriculture.

ASEAN therefore uses its institutional platforms to fight against climate change. In this regard, cooperation with the European Union is particularly relevant. In addition to the contribution of multilateral institutions, last November ASEAN held a broad dialogue on climate change and international responsibilities, when their respective commitments were reiterated. In the wake of the European Green Deal, Southeast Asia can use on the long-standing experience of the Union on the subject of regulations against the abuse of plastic, and for the promotion of biodiversity and the circular economy. The cooperation between the two regional entities is also supported by the Enhanced Regional EU-ASEAN Dialogue Instrument, within which dialogue between countries is promoted in various areas of interest, including sustainability, environment and climate change. As Vandana Shiva argues, expert in social ecology and environmental activist, in order to imagine a sustainable future for our planet, a paradigm shift is essential, no longer based on the predation of environmental resources or on unregulated competition, but on the sharing of information, practices and responsibility. In this sense, ASEAN-EU inter-regional cooperation represents a real opportunity to be able to imagine alternative models of socio-economic development, in the name of the respect for the environment.

By Agnese Ranaldi