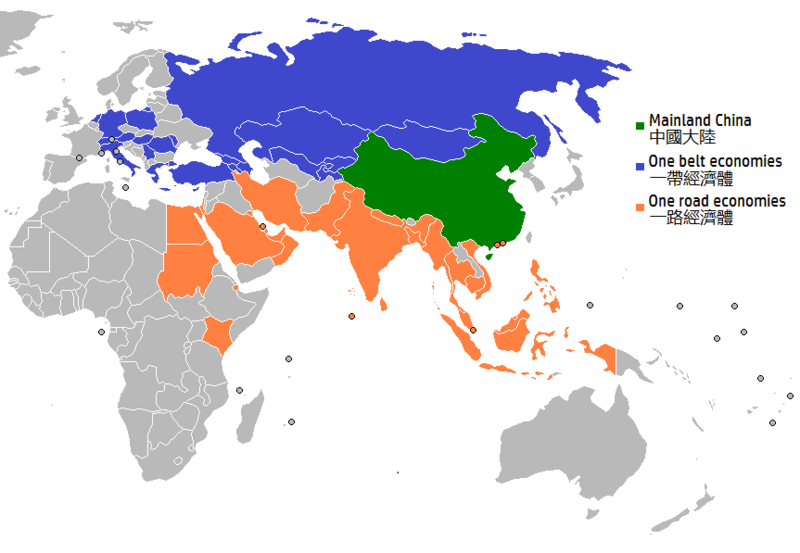

In the new and complex geopolitical scenario, both the US and ASEAN have an interest in rediscovering their mutual strategic importance.

The relationship between the United States and South-East Asian countries has undoubtedly been at the heart of the creation and development of ASEAN since the late 1960s. Although the Association of Southeast Asian Nations was born in 1967 out of the community-oriented impulse of its five founding members and out of their common attempt to halt the advance of Soviet communism in Southeast Asia, it is clear that the United States’ contribution has been fundamental for ASEAN’s development. The common anti-Soviet sentiment made ASEAN a valuable American ally in East Asia in the 1970s and 80s: it is in fact no coincidence that in May 1986 the then-President of the United States Ronald Reagan defined “support for and cooperation with ASEAN […] a linchpin of American Pacific policy”. However, the end of the Cold War represented the end of the honeymoon between the United States and ASEAN. Although formally the relations between the two blocs never ceased, the collapse of the USSR marked the end of the expansion of Soviet communism, thus eclipsing Asia among American strategic priorities. Soon enough though, as early as the mid-2000s, the emergence of international terrorism and, more markedly, China’s comeback on the global geopolitical scene, forced the US to reassess the strategic importance of Asia-Pacific and, therefore, of ASEAN. The advent of the Obama administration certified this change of pace in American politics. In fact, breaking patterns with his last predecessors, Obama immediately recognized the centrality of the Asia-Pacific region and plainly stated that ASEAN would come to shape the 21st century.

However, the rediscovery of Southeast Asia for the United States is not purely geopolitical. In fact, ASEAN represents the US’ fourth largest trading partner, with a total volume of exchanged goods and services of over 330 billion dollars in 2018 alone. ASEAN runs a trade surplus with the United States of over 85 billion dollars per year and has been a privileged destination for US FDI, for a total stock of over 271 billion dollars to date. The growing economic weight of ASEAN, combined with its immense potential to balance Chinese ambitions in the region, render it a natural ally fot the US in the Asia-Pacific region. Similarly, the United States represent a valuable commercial partner and a useful geopolitical ally for ASEAN. By virtue of the US’ status as ASEAN's third commercial partner and thanks to its essential role in maintaining a stable balance of power in the Pacific region, both of which are vital elements for the long-term prosperity of the Association, South-East Asian countries have an interest in maintaining a strong and lasting relationship with the US, both on the economic and international relations terms. However, the recent advent of Donald Trump to the White House has contributed to further changing the scenario. The skepticism of the current US President towards multilateral solutions, which prompted him to sit out the US-ASEAN summit twice, made many people turn up their noses in South-East Asia. Despite the innate bilateralism that drives Trump's political agenda, however, the American diplomatic-military apparatus knows well the strategic importance of ASEAN for the United States. These two souls determine a certain ambivalence in US approach to South-East Asia, which has manifested itself several times, even within the Trump administration itself. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo not only reiterated his full support for ASEAN regional institutions, but on the occasion of a joint video-conference held on April 22 between the representatives of the two powers to discuss the effects of the Covid-19 crisis, he launched the “US-ASEAN Health Futures initiative”, a $35 million plan designed to support ASEAN countries in the fight against coronavirus, which adds to the over $3.5 billion that the US has already invested in the South-East Asian health sector in the past 20 years.

With the end of the Cold War and the bipolar world order, relations between the United States and ASEAN have experienced more than three decades of ups and downs. The complex, at times ambiguous, American strategy in the Pacific has led to a dynamic and evolving relationship between the two. However, if ASEAN and the United States wish to maintain their presence in the Pacific, they must necessarily rediscover each other's economic and geopolitical centrality, collaborating to build a more balanced regional and international system.

Article edited by Andrea Dugo.