Cambodia’s last experience in the rotating presidency has been controversial, as foreign policy of the Asian kingdom particularly prefers the relation with Beijing

The rotating presidency at the ASEAN is a great opportunity for the diplomacy of Southeast Asian countries. 2022 is the Cambodia’s turn, ready to work for the creation of a “fair, strong and inclusive” regional community, under the leadership of Prime Minister Hun Sen. The head of the Cambodian government has shown that takes this commitment seriously and has declared that the Association’s “policy and security” pillar will be at the top of the agenda during his mandate at the regional organization. What awaits it in 2022 is experienced as a prestigious honor for Phnom Penh, that will use the occasion to amplify his diplomatic aura and enjoy prerogatives associated with the presidential title, as the renovated recognition from major players of the world.

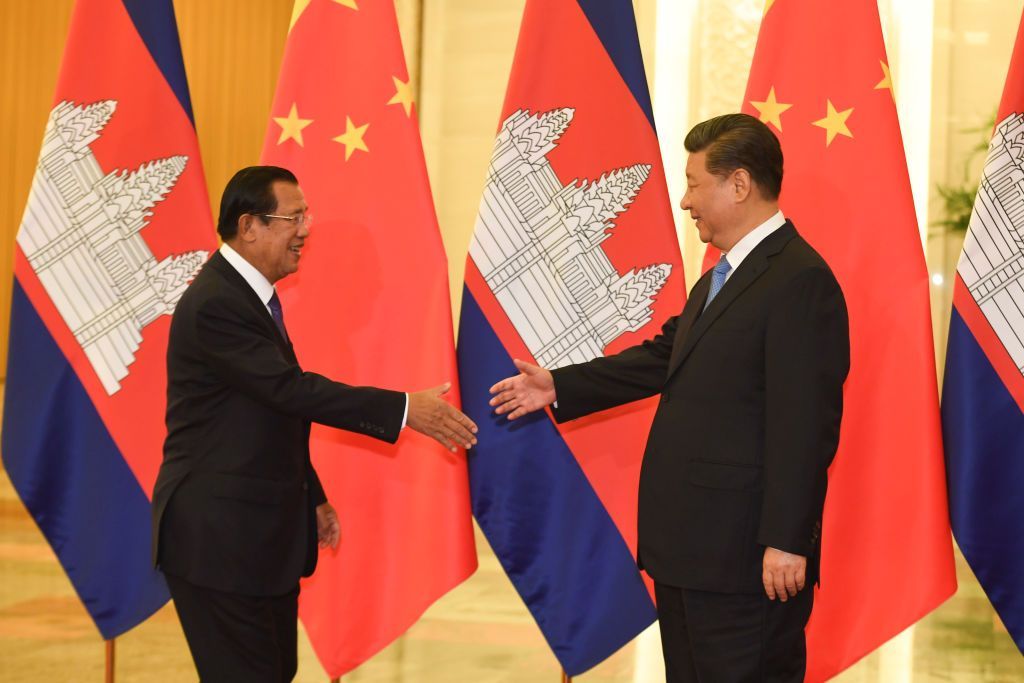

But, in the international community, the enthusiasm is not as widespread. Cambodia’s last experience in the rotating presidency has been controversial, as foreign policy of the Asian kingdom particularly prefers the relation with Beijing. This historic pro-Chinese posture was also vindicated by the national government in 2019, when Prime Minister Hun Sen defined Cambodia as an “iron friend” of China. It is precisely because of this proximity that, according to analysts, we can expect a very different ASEAN compared to the one left by Brunei in 2021. According to expert voices, while most of the Southeast Asian countries distance themselves from Beijing criticizing its adversity, Phnom Penh stays loyal to the bandwagoning line: due to security and development issues, China remains a fundamental ally for the Cambodian regime, and this connection could compromise the unstable balance of the regional Association.

The most relevant files of 2022 call into question the ASEAN centrality in managing the Covid-19 health crisis and in the regional and international trust towards the most pressing political controversies. Cambodia will succeed Brunei after a year full of criticality, inheriting political and social challenges caused by two years of global pandemic, Myanmar’s political crisis and the long-standing diatribes in the South China Sea. But according to Charles Dunst of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Beijing’s incumbency could undermine the Cambodian freedom of maneuver on these topics, resulting in a dangerous immobilism of the Association. This could deal the deathblow to the ASEAN’s principle of centrality, already compromised by the tendency of other international players to prefer bilateral relations with countries in the area.

Regarding challenges caused by the pandemic, worsening social inequalities are likely to cause political instability everywhere in Southeast Asia. Phnom Penh will also have to deal with the increase of global interest rates that in many regional economies will cause an increase in fiscal pressure and limit expansive public policies, causing discontent and economic suffering in local communities. In this regard, the bilateral relation with China is crucial for Cambodia, which heavily relies on its big brother’s aid and infrastructure funding for its national development programs.

About Myanmar’s crisis, Cambodia has then assumed bivalent behaviors. After strongly reiterating the principle of non-interference claimed by ASEAN as the cornerstone of its paradigm of values, he then supported the Association’s decision to not want to confront except with “non-political” representatives of Myanmar. Prime Minister Hun Sen has declared in this regard: “ASEAN has not expelled Myanmar from ASEAN”. Myanmar has abandoned its right (…). Now we are in a situation of “ASEAN less one”. It is not so because of ASEAN, but because of Myanmar itself. According to Dunst, however, Cambodia does not consider it a priority to confront the Burmese regime on issues of democracy and human rights. That’s why on Myanmar, ASEAN’s next first voice may turn out to be weaker than hoped for by other member countries, such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

Instead, territorial disputes in the South China Sea are the elephant in the room for the Cambodian presidency, and it seems that the experience of the 2012 mandate could be repeated. At the time, as now, Cambodia and China have preferred to use bilateral mechanisms of dispute resolution. According to Vannarith Chheang, researcher associated at the IASEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, the promotion of code of conduct (CoC) in the South China Sea is a way to avoid cumbersome binding measures and encourage so-called preventive diplomacy. “Cambodia is not interested in internationalizing the South China Sea issue”, the analyst notes in an article in the Turin Would Affairs Institute’s journal, “and is cautiously restricting other suitors such as Vietnam and the Philippines from using ASEAN to directly counter or challenge China”. At the annual summit of ASEAN representatives, held last November 22nd, President Xi Jinping also intervened by videoconference, reassuring those present that China would never seek hegemony in the region by taking advantage of its strength to resolve disputes. Rather, stressed the Chinese Communist Party secretary, the hope is that ASEAN will be able to cooperate with China to eliminate foreign “interference”. Xi’s words seem to prophetically welcome the arrival of Phnom Penh as president of the organization. Although ASEAN and China have already agreed on the preamble to the CoC in the summer of 2021, Cambodia could slow down its negotiation process by protecting its historic friendship with Beijing and limiting any actions or statements by the ASEAN bloc that might imply a criticism of Chinese assertiveness.

The Cambodian presidency’s approach to challenges most relevant to Southeast Asia will also affect tones and preferences of international cooperation. According to David Hutt, of The Diplomat, the fact that the kingdom is considered a “pariah for democracies” and its reputation is that of “Beijing’s lackey”, also affects the foreign policy of major international players. On the one hand, it is the goal of the Biden administration to rally its allies to maintain greater control over the regional dynamics of Indo-Pacific Asia. Think of the emergence of the AUKUS defense alliance, stipulated by the US, the UK and Australia, which is programmatically designed to curb China’s international ambitions. The infrastructure program for post-pandemic recovery, the Build Back Better World (B3W) is a clear antagonist to the global development strategy, promoted by Xi with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Biden then took a more uncompromising attitude toward Cambodia itself, having sanctioned two senior officials for corruption and announced a review of preferential trade agreements last month. About the EU, Phnom Penh hosted the 13th Asia Europe Meeting (ASEM) on November 25th and 26th, demonstrating the renewed European interest in opportunities offered by Southeast Asia, reaffirming the partnership with the regional counterpart organization. Among all, the one with the Union could prove to be a strategic link for ASEAN, to weigh Cambodia’s contested pro-Chinese tendencies and devote itself to enhancing relations with another important regional player.

Always in the orbit of Chinese influence, Cambodia will conduct its mandate as president of ASEAN under the banner of “iron relations” with Beijing. Although some analysts believe that Hun Sen’s government is now less willing to accept China dictating the terms of its foreign relations, challenges facing ASEAN in 2022 all confront Cambodia with a choice: with Beijing or against Beijing. Judging from the historical bond, made all the stronger by the common colonial past and shared political culture, it seems that the direction of the Cambodian presidency at ASEAN is already marked.