As economic interactions grow, the risk of Chinese commercial hegemony in the region arises

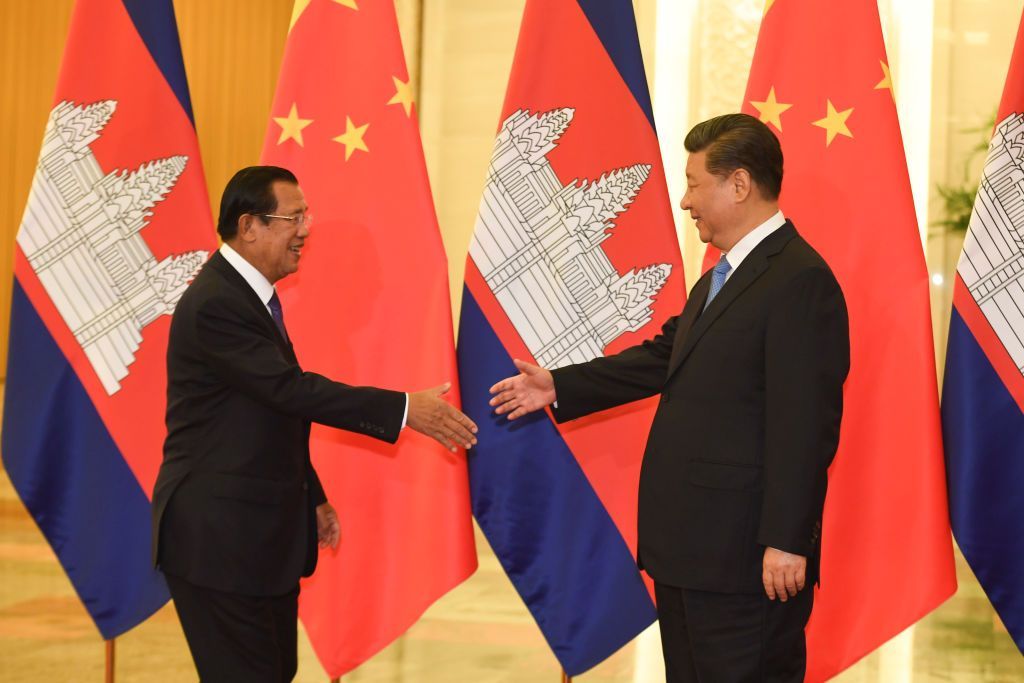

Good neighbourhood policies have become the priority of the Chinese government for the years to come. In order to tackle the diplomatic isolation pushed by Washington in the ongoing commercial spat between the two powers, Xi Jinping focused on strengthening economic ties with Southeast Asian countries, the most important hub for China's global projection. This policy has been confirmed by the recent visit of the Chinese foreign minister, Wang Xi, to Myanmar, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippin. During this mini tour of ASEAN, Wang Xi reiterated the importance of a strengthened cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, aimed to overcome the health emergency and, above all, in prospective of the major coordination with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the masterful Chinese initiative aimed at improving infrastructural connections with Eurasia.

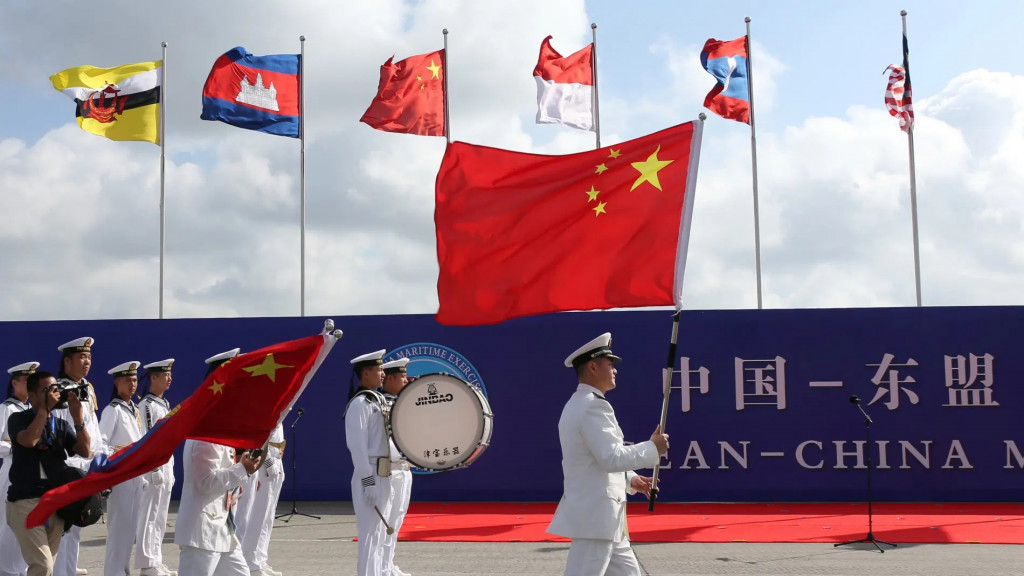

Historically, relations between Beijing and the ASEAN countries have not always been idyllic. However, since the 1990s there has been a progressive economic and diplomatic rapprochement between the parties, culminated in the 2002 free trade agreement. Since then, China has not stopped courting ASEAN and other Indo-Pacific countries to further consolidate economic cooperation. Finally, in 2020, after eight years of negotiations, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed; a historic agreement that gave birth to the largest trading block in the world, capable deeply influencing the global economic balance. The signatories are the 10 ASEAN members plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, but not the United States, whose exclusion is a clear sign of their strategic loss of weight in the region.

The agreement’s timing is not accidental; it is the consequence of the health and economic crisis that hit the whole world, with the exception of China, the only G20 country with positive GDP growth in 2020. Indeed, since long ago Beijing has been pushing for a deeper economic interconnection with Southeast Asian countries. This trend, oriented towards privileged regional cooperation has been confirmed by the continuous growth, despite the health emergency, of the commercial exchanges between Beijing and the ASEAN countries, which have become China's major trading partner, surpassing the European Union. If, in fact, trade has increased by 7% compared to previous years, bilateral investments also marked a significant increase, reaching + 58% compared to 2019..

However, there is a downside: Beijing's recovery from the pandemic, faster compared to the rest of the world, with a prospect of 8% growth in 2021, in addition to the greater commercial influence in Southeast Asia acquired thanks to the RCEP, could make ASEAN countries increasingly dependent on the exports and foreign investments of its powerful neighbour. Especially after India’s decision to abandon the negotiations, China is the hegemonic actor of the agreement. Nonetheless, the benefits are numerous; by exploiting the complementarity of the different economic systems, the ASEAN countries with the support of the other members, will be able to more easily create regional value chains and will become a privileged destination for foreign direct investments, especially from Japan and South Korea, thus rebalancing Chinese influence. This will ensure an increase in the industrial capacity of the ASEAN countries and, in the long run, also a probable decrease in the average income gap in the region.

In reality, the tendency to reallocate investments to ASEAN countries is not new; for some years, in fact, there has been an increase in FDI from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan higher than the share sent by the same countries to Beijing. This is mainly due to the increase in labour costs in China, but also linked to the need to diversify the production chain. Indeed, the inclination to reconsider the economic centrality of ASEAN is increasing; thanks also to the effective containment of the health emergency, this area of the world has not experienced significant economic and trade deficits. The case of Vietnam is peculiar; with a GDP of 2.6% higher than in 2019 it confirms itself as the only Asian nation, together with China, to have presented a constant economic growth during the health emergency. Yet, there is more. The economies of the whole region are expected to increase in 2021, particularly for Indonesia (+ 6.1%), Cambodia (+ 6.8%), the Philippines (+ 7.4%) and Malaysia (+ 7.8%)..

In conclusion, the world axis is moving eastward. Beijing is aware of this and does not hesitate to utilize its privileged position to carve out a leading role in the new scenario, bringing the ASEAN countries with it. For Southeast Asian countries, the goal will be to seek a delicate balance to secure their manoeuvrability in the continent and to continue to attract investments, without increasing too much Chinese influence in the region.

By Emilia Leban